Abstract

Protests advocating for progressive social change sometimes face opposition from counter-protests defending the status quo – but how do these clashes shape public opinion? In this research, we investigated whether and how counter-protests influence support for social change. We conducted five survey studies using correlational and experimental designs in different socio-political contexts: pro-democracy Hong Kong solidarity protests (Study 1: N = 311 students in Australia), Thai anti-monarchy protests (Study 2: N = 269 Thais), U.S. immigrant rights protests (Study 3: N = 381 U.S. Americans) and Australian environmental protests (Study 4A: N = 129 Australians, Study 4B: N = 268 Australians). Overall, we found evidence that social change protests disrupted by a violent counter-protest heightened concerns that the counter-protesters were suppressing the initial protesters’ expressions of free speech. This in turn was associated with greater sympathy towards protests for social change. Although counter-protests often aim to undermine a cause, our findings suggest their actions might ironically promote more public concern for social change protesters. This research has implications for understanding protest and counter-protest dynamics: it highlights the importance of considering public opinion beyond a single protest context and the role of public attitudes in driving social change.Key Takeaways

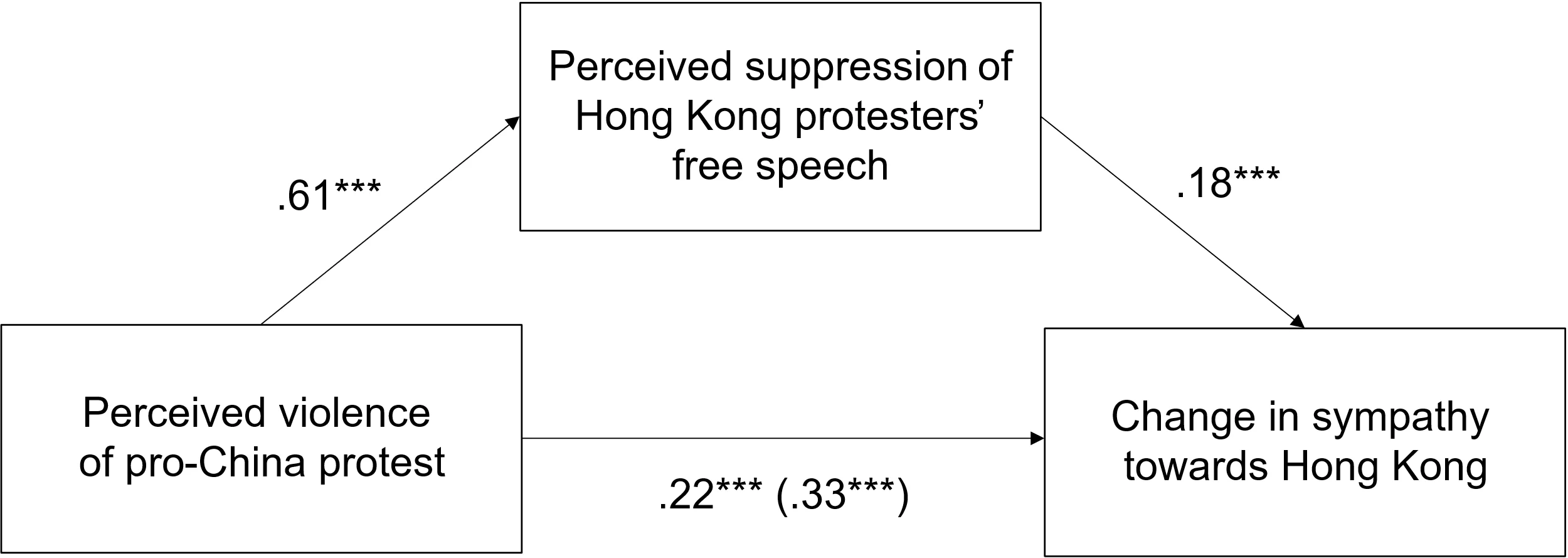

- Across Study 1 (Australian campus clash) and Study 2 (Thailand), people reported more sympathy for system-challenging protests when counter-protesters were seen as violent. In Study 1, perceived counter-protest violence predicted higher perceived free-speech suppression (b = 0.61, p < .001), which in turn predicted greater sympathy for Hong Kong protesters (b = 0.18, p < .001; indirect b = 0.11, 95% CI [0.05, 0.19]). Study 2 replicated this pattern for Thai pro-reform protests (indirect b = 0.06, 95% CI [0.01, 0.13]).

- Self-reported sympathy shifts were sizable and statistically robust. In Study 1, sympathy increased for Hong Kong (t(304) = 13.82, p < .001, d = 0.79) and decreased for China (t(304) = −18.23, p < .001, d = −1.04). In Study 2, sympathy increased for pro-reform protests (t(264) = 22.82, p < .001, d = 1.40) and decreased for anti-reform protests (t(260) = −15.30, p < .001, d = −0.95).

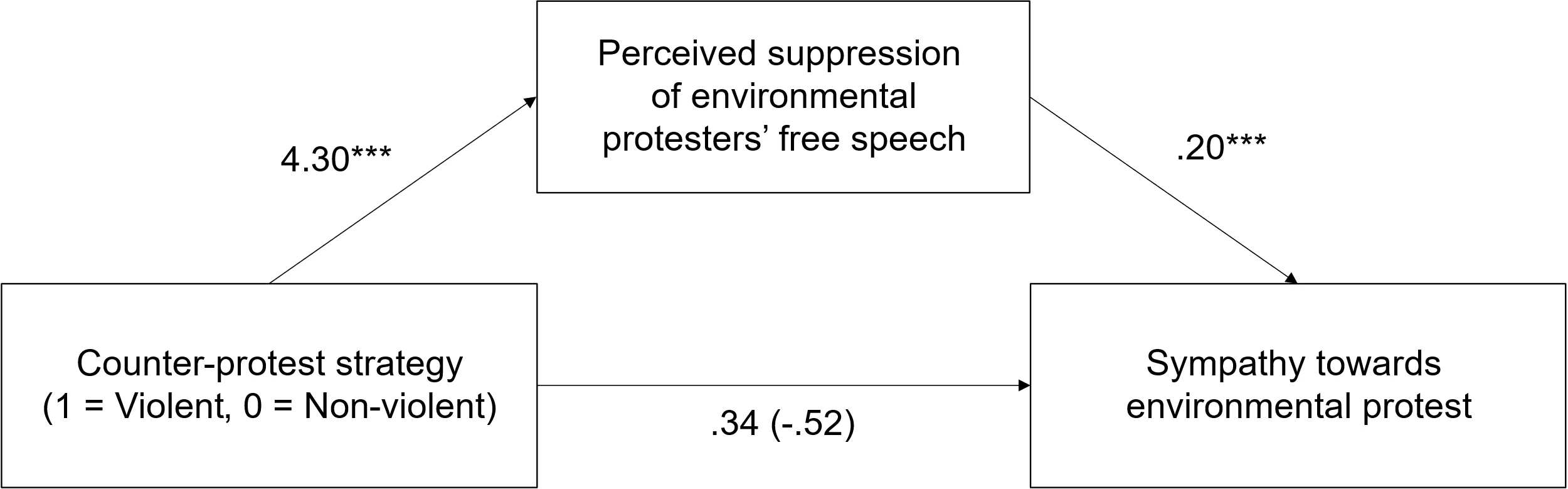

- Study 3 experimentally showed that a violent White nationalist counter-protest heightened perceived suppression of immigrant-rights protesters’ free speech (M = 6.95 vs. 3.51) and boosted sympathy for the immigrant-rights protest (interaction F(1,376) = 4.10, p = .044). Mediation supported the free-speech pathway: violent (vs. non-violent) counter-protest increased suppression perceptions (b = 3.60, p < .001), which was associated with sympathy (b = 0.20, p < .001; indirect b = 0.73, 95% CI [0.45, 1.10]).

Author Details

Citation

Selvanathan, H.P., Hornsey, M.J., Jetten, J., Bourdaniotis, X.E., Hewett, M., & Manoharan, R.T. (2026). Understanding public responses to counter-protests disrupting social change movements. advances.in/psychology, 1, e648056. https://doi.org/10.56296/aip00049

Transparent Peer Review

The present article went through one round of double-blind peer review. The peer review report can be found here.